ARE KINDERTRANSPORT CHILDREN

IN 1939 AND 2016 THE SAME?

NO

In 1939

Parents put their children on a train

looking forward to see them again

In 2016

These children are alone.

Their parents and family were lost in warfare

OUR QUESTION

Do we want to help these children?

IF YES

We need to find families willing to give them a home

We need to behave like the Quakers in 1939

We need to behave like the Attenborough family.

1989 12th June

Sidney Samuelson, Esq.,

You asked me to let you have some gen about my two adopted sisters. My father chaired a committee when Principal of Leicester University College devoted to bringing Jewish refugees out of Hitler's Germany. In a large number of cases it merely meant housing them for a relatively brief period of time while they obtained visas to go to relatives in either the United States or Canada (this applied particularly to children).

On the particular occasion, my Mama - known as Mary, my father being known as the Governor - went to London to collect two girls whose father was one of the medical officers for Berlin. They arrived back home, Irene aged 12 and Helga 9, the former with a dreadful nervous mannerism and the latter almost covered in sores.

As far as my two brothers and I were concerned, they were just two further lost children who seemed to inhabit our house every few weeks. However, the difference was that during their time with us, war was declared. One day on our return from school, David, John and I were asked to go and see the Governor in his study. Mary was also there. They both explained to us that the two girls who were at present staying in the house were by virtue of the threatened war totally stranded. They had little news of their father, their mother and elder sister were in concentration camps (perhaps I should add that by some miracle their elder sister survived, but they never saw their mother or father again). Equally there was now no possibility of a visa to go to America and so Mary and the Governor had decided that with our agreement the two girls should remain with us for as long as the war lasted and until they could rejoin their family. My parents were adamant that there was only one condition under which this was possible and it was that they should to all intents and purposes adopt the two girls. It would mean, they explained, that we would no longer be a family of five but a family of seven, and that the family would only engage in any form of activity - holidays, outings, supply of clothes etc - that we could afford as a family of seven. The girls would be treated in exactly the same way and that my parents would love them as they loved their three sons. In other words, they were to become our ''sisters” on a totally equal standing with the three of us, the only difference being that whereas we referred to Mary and the Governor as Mother and Father, the girls would call them Aunt and Uncle, naturally in the expectation that they would eventually be reunited with their own parents.

The decision, the Governor said, is up to you boys. If they are to live with us, your Mother and I are convinced that this is the only proper way in which we should anticipate the future. Naturally the three of us agreed at once and I am sure David and John would agree that it was one of the best decisions we have ever made.

We became devoted to Irene and Helga and have remained so for the last 50 years. They both live in the United States now, both were married (although sadly Irene’s husband Sam Goldschmit has died), but Helga remains married to Herman Waldman and they have two daughters.

So, my dear Sydney, that is how David and John and I came to acquire two sisters.

From

Lord (then Sir) Richard Attenborough C.B.E

ADDRESS

FORMER CHILD REFUGEES, RESCUED FROM NAZIS,

URGE U.K. TO TAKE SYRIAN KIDS

LAUREN FRAYER May 9, 20162:53 PM ET Heard on All Things Considered

Margit Goodman (left) and her daughter Karen Goodman are lobbying the British government to take in Syrian refugee children. Margit Goodman, now 94, was one of nearly 10,000 children rescued from the Nazis by Kindertransport, a program sponsored by the British government and Jewish aid groups in the lead-up to World War II.

Lauren Frayer/NPR

In her suburban London row house, Margit Goodman, 94, sits wrapped in blankets in her favorite recliner.

She was a girl of 17 when she first came to Britain, escaping from her native Prague just before the Germans invaded. She remembers the exact date: June 5, 1939.

"When I left, [Czechoslovakia] was still a free country," she recalls. "But we soon became occupied by the Germans."

In the late 1930s, as Nazi persecution of Jews intensified, the British government and Jewish aid groups arranged for the transport of nearly 10,000 children to the U.K. from Europe, through a program that became known as the "Kindertransport."

Goodman was one of the children rescued by the program. "I wouldn't be here now. They saved our lives, didn't they?" she says.

Her mother, father and brother were left behind in Prague. From there, they were deported to concentration camps — where they were gassed to death.

Goodman arrived in London alone. No other close relatives survived.

"I've never seen a photo of my grandparents," says Karen Goodman, Margit's daughter.

Margit Goodman ended up working as a house maid in Scotland. Her experience as a teenage refugee shaped her whole family. She eventually became a social worker, and so did her daughter.

Now both women have become advocates for today's child refugees from Syria.

In November 1938, the British Parliament passed emergency legislation to admit Jewish child refugees from Europe without visas. The Goodmans and a number of former evacuees, now elderly, are lobbying the U.K. to do the same for unaccompanied Syrian children who are in Europe.

Karen Goodman recently briefed members of Britain's Parliament on how the U.K. social services system might absorb 3,000 Syrian youngsters through programs like the one to which her mother says she owes her life.

But Prime Minister David Cameron has said he doesn't want his government to grant asylum to any Syrian refugees who've already traveled to Europe on their own.

"We shouldn't be encouraging people to make this dangerous journey," Cameron told Parliament last week. "I think it's right to stick to the idea we keep investing in the refugee camps and in the neighboring countries." Cameron's ruling conservatives voted against an immigration bill amendment last month that would have forced his government to bring in 3,000 Syrian child refugees already in Europe.

Dozens of his fellow evacuees have asked Cameron to change his mind. The prime minister has since said he's willing to reconsider and admit some Syrian children, but he wouldn't give a number.

"My survival is entirely due to the extreme generosity of the British government in 1938," says Leslie Brent, 90. "And the contrast with the present government is quite pathetic."

Brent says he's worried Cameron is caving into pressure from right-wing, anti-immigrant groups. His Conservative Party is already split over a possible British exit from the European Union, on which Britons will vote in a national referendum in June. Immigration — or fear of it — is a big part of that debate.

Brent recalls how in the 1930s, anti-Jewish sentiment got so bad in his hometown in northern Germany that he could no longer go to school. So his parents sent him to an orphanage in Berlin. That decision helped save his life.

"The director of the orphanage nominated me to leave on the first Kindertransport, which left Berlin on the first of December 1938 — only a few weeks after Kristallnacht, the night of the broken glass, when Jewish shops and homes and synagogues were ransacked," he says. "My parents had until then really believed that things would change for the better."

They did not. Brent's parents and older sister were shot by the Nazis. Brent attended a Jewish boarding school in Kent and then served in the British army during World War II. He later won a grant to go to university, earned a Ph.D. and became a professor of immunology — contributing to work that won a Nobel Prize in 1960.

"I don't know anyone who came over on one of the Kindertransports who hasn't more than repaid the generosity of Britain in one way or another," he says. "And I have little doubt that these modern refugee children would act in the same way. Everyone thinks of them as a nuisance and a burden."

Brent says he is living proof of how mistaken that belief can be.

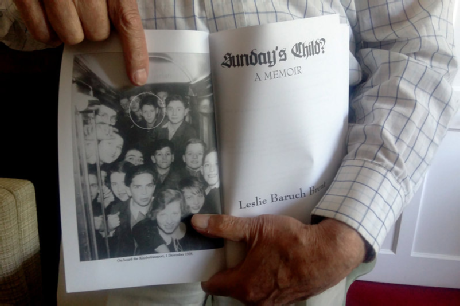

"I don't know anyone who came over on one of the Kindertransports who hasn't more than repaid the generosity of Britain in one way or another," says Leslie Brent, 90, a retired immunology professor. "And I have little doubt that these modern refugee children would act in the same way."

Lauren Frayer/NPR

Leslie Brent, 90, a retired immunology professor who came to Britain as a Jewish child refugee via Kindertransport in 1938, holds his autobiography, showing a photo of himself and other Kindertransport children.

Lauren Frayer/NPR

The amendment was authored by Alfred Dubs, a Labour Party member of the House of Lords who, like Margit Goodman, was born in Prague and came to Britain as a child refugee via Kindertransport.